This is a completely reasonable question but it's not so easy to answer. There's not a concrete answer, no black-and-white time limit each student should adhere to.

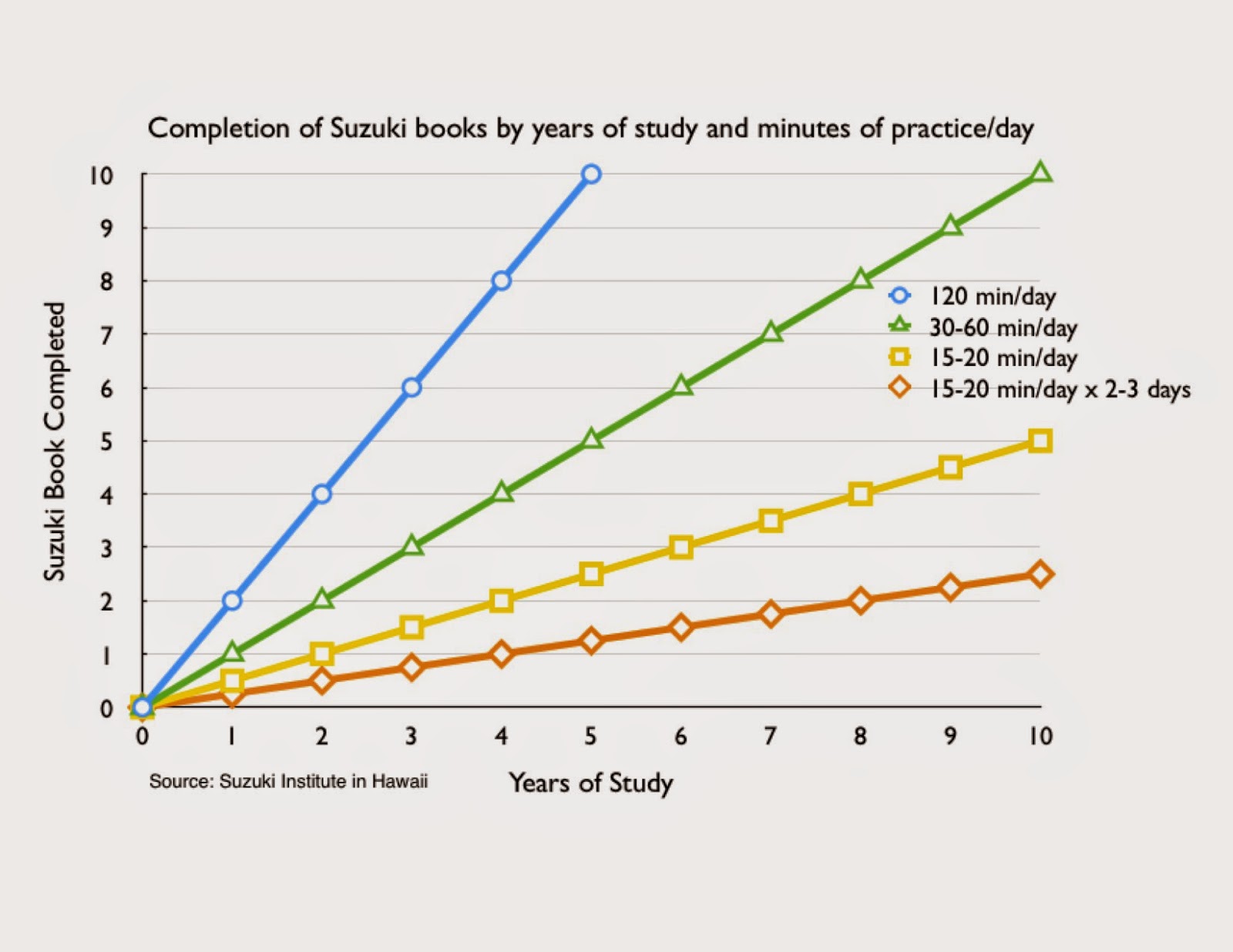

Many of my students have seen this graph in my studio:

While this does give a lot of information on the effect of length of practice on progress, it doesn't quite tell the whole story. Duration and frequency of practice is important and there certainly is a relationship between practice duration, practice frequency and progress. But duration and frequency are not the only aspects that determine progress and success in learning a musical instrument.

First off, how do you define progress? I try to de-emphasize the notion that progress is simply moving through the books and learning the next piece. First, progress looks differently for every kid. Also, progress in learning a musical instrument involves much outside of learning the next piece in the book. Progress for me means a number of different things. Progress means:

- deeply, very deeply, learning skills

- the ability to transfer current knowledge and skills to new domains

- learning how to figure things out on your own with limited outside help

- one day not needing me as a teacher (yes, I am essentially trying to put myself out of a job)

Progress is an overall increase in the educational well-being of the student and helping develop the student into a well-rounded musician and human being.

Progress does not only mean learning the next piece and then the one after that.

Looking closely at the graph, it indicates that a student who practices two hours a day will learn 2 books a year. In my experience, Book 1 takes the longest for most students to finish. It's the foundation book and I like for students to take 2 years to complete Book 1. That way all those foundation skills and techniques are rock solid and building on those skills won't result in a total collapse or frustration. To list them all would take quite a while, but they include:

- focus

- singing

- hearing pitch

- holding the cello properly

- holding the bow

- using the bow correctly on the cello

- playing with a good tone

- playing in tune

- adjusting when out of tune

- playing on all four strings

- playing with different finger patterns

- staccato, legato, marcato,

- preliminary shifting exercises

- fingerboard geography

- note reading

- tuning the instrument

- playing with others, etc.

WHEW. That's a lot of skills. And that doesn't even come close to covering them all. Book 1 takes time. Yes, it's tedious and Twinkle is borderline painful because it takes a long time but your child will greatly benefit from fastidious development of knowledge and skills. It's hard to see it in the moment but just know there is light at the end of the Twinkle tunnel.

As for learning two books a year with 2 hours of practice, sure, it's possible. But there are lots of other things that students need to learn outside of the Suzuki repertoire that will take time away from strictly getting through the books. For example, there are several pieces and technique books outside of the Suzuki repertoire I incorporate in my curriculum to develop well-rounded and artistic musicians.

The Suzuki books are great but solely focusing on achieving completion of those books is akin to trying to become a well-rounded chef by only cooking through one series or one style of cookbooks. There is more knowledge that needs to be learned from other sources. Yes, this takes more time but it's worth it for the development of well-rounded musicians and accomplished learners.

Also, many students start between the ages of 3-6. Can you really get a 3 year-old to practice for 2 hours? Nope. How about a 6 year-old? Probably not. Not only is it hard to get a little one to focus and pay attention for long periods of time, they simply do not have the physical endurance to withstand long practice sessions. It ain't gonna happen. That isn't to say a highly dedicated 7 year-old can't devote 2 hours daily to practice but I think that delves into other issues I'd rather not get into here. I believe kids should be kids. Enough said.

***

If practice isn't determined by a set time limit, than what should it be determined by?

Goals. More specifically, the setting and achievement of specific goals within a given practice session. This may take more time at first but practicing without setting a goal is a lot like getting into your car without a destination in mind. You end up driving around in circles for a long time before (maybe) arriving where you want to be. And you waste a lot of time. I'm not about wasting time.

Practice, lessons and rehearsals are made up of many, many aspects. But what we need to do as teachers and parents is help break everything down into the smallest unit of learning, identify accomplishable goals and set up students to accomplish those goals.

Set achievable goal and accomplish that goal. Don't mindlessly play through everything without a goal in mind for each piece. Even if the goal is to review, make the goal 'review with a good bow hold' or 'play review pieces with the best sound possible'. And remind your child about the goal or point before they play each piece. This will bring a very different focus to the practice and also results in less frequent messy repetitions of the pieces. Every messy or sloppy performance is a reinforcement of that skill. Please avoid this! We don't want to reinforce poor cello playing!

Here's a few examples of clearly defined practice goals:

- Practice the preview spot in Song of the Wind 10 plucked times or until it looks easy for the fingers, with clear, ringy notes every time.

- Practice the shift in Minuet No. 2 12 times with a moving thumb and in-tune G#.

- Practice the 3rd section of Perpetual Motion until it feels easy and effortless before playing the whole song. Then add it to the rest of the song.

- Practice the bowing in line 1 of Minuet in C 6 times, in a row. If there is a mistake in one, add an additional repetition, making it 7, etc.

- Play Mississippi Stop Stop Twinkle for good, clean 'stops' on every Mississippi Stop Stop.

- Practice X piece until it feels easy, not until it's correct.

My goal for every practice is to make any given skill easy rather than getting it right. Getting it right once does not mean the skill is learned. However, practicing something for ease automatically ensures it will be correct and repeatedly correct because it's effortless to execute.

If you achieve your predetermined practice goals in 12 minutes rather than the 30 minute you budgeted for practice, fantastic! Go read a book for the remaining 18 minutes. Or practice more! Set another goal and achieve it! You and your child will find this practice much more motivating than playing through everything. The goal was determined and was met - that's a pretty exciting thing! And it makes students want to come back for more because it's such a positive and rewarding experience, much more so than just playing through Allegretto mindlessly thinking about what's for dinner.

***

Next time you pull out the cello to practice with your child, work with your child to determine accomplishable goals at the start of practice or before you start something new during the practice.

Start small. Start with something achievable in a short amount of time - think 90 seconds to 4 minutes maximum. Yup, that short. Don't bite off more than you both can chew. Setting the goal to learn all of Etude when you only have the first 4 notes is setting yourselves both up for failure and disappointment.

Celebrate! Praise your child (and yourself!) on achieving the pre-determined goals.

Happy (goal directed) practicing!

Thanks. That was helpful 67 year old beginner cello student.

ReplyDelete