I read a lot of books on psychology, specifically educational psychology. One really great book I'd like to share is Mindset by Dr. Carol Dweck. I was first introduced to Dr. Dweck's work a number of years ago at a Suzuki conference where she gave the keynote speech. Her presentation showcased her fascinating work and findings, many of which have stuck with me, most particularly because I felt I had experienced my own mindset shift during that same year. I hadn't realized I had undergone a mindset shift until it was defined and I learned about her work. I later read her book, which delves into much of this same research but in a much more approachable writing style. I highly encourage you to read this book - I have two copies to share - but hopefully this 'book report', if you will, gives you an idea of Dr. Dweck's fascinating research.

The basic premise of Dr. Dweck’s book is fairly simple: the attitudes and beliefs with which people view themselves guides a large part of their lives. These beliefs strongly affect interactions with other people as well as how successful people are in school, work as well as other domains.

***

The basic premise of Dr. Dweck’s book is fairly simple: the attitudes and beliefs with which people view themselves guides a large part of their lives. These beliefs strongly affect interactions with other people as well as how successful people are in school, work as well as other domains.

“Our mindset is not a minor personality quirk. It creates our whole mental world. It explains how we become optimistic or pessimistic. It shapes our goals, our attitude toward work and relationships, and how we raise our kids, ultimately predicting whether or not we will fulfill our potential.”—Dr. Carol Dweck

People either exercise a growth mindset or a fixed mindset. Those with a fixed mindset believe their talents and abilities cannot be improved through any means. They believe they are born with a certain amount of talent and do not wish to challenge their abilities or push themselves beyond their capabilities due to the possibility of failure. Individuals with a fixed mindset frequently guard themselves against situations in which they feel they need to prove their personal worth. Challenges are frequently viewed negatively, instead of as an opportunity for personal growth and people with a fixed mindset often feel the need to prove themselves. Lastly, people with a fixed mindset believe if you have an ability, then learning isn't necessary, that ability should show up without any effort at all or there is no ability.

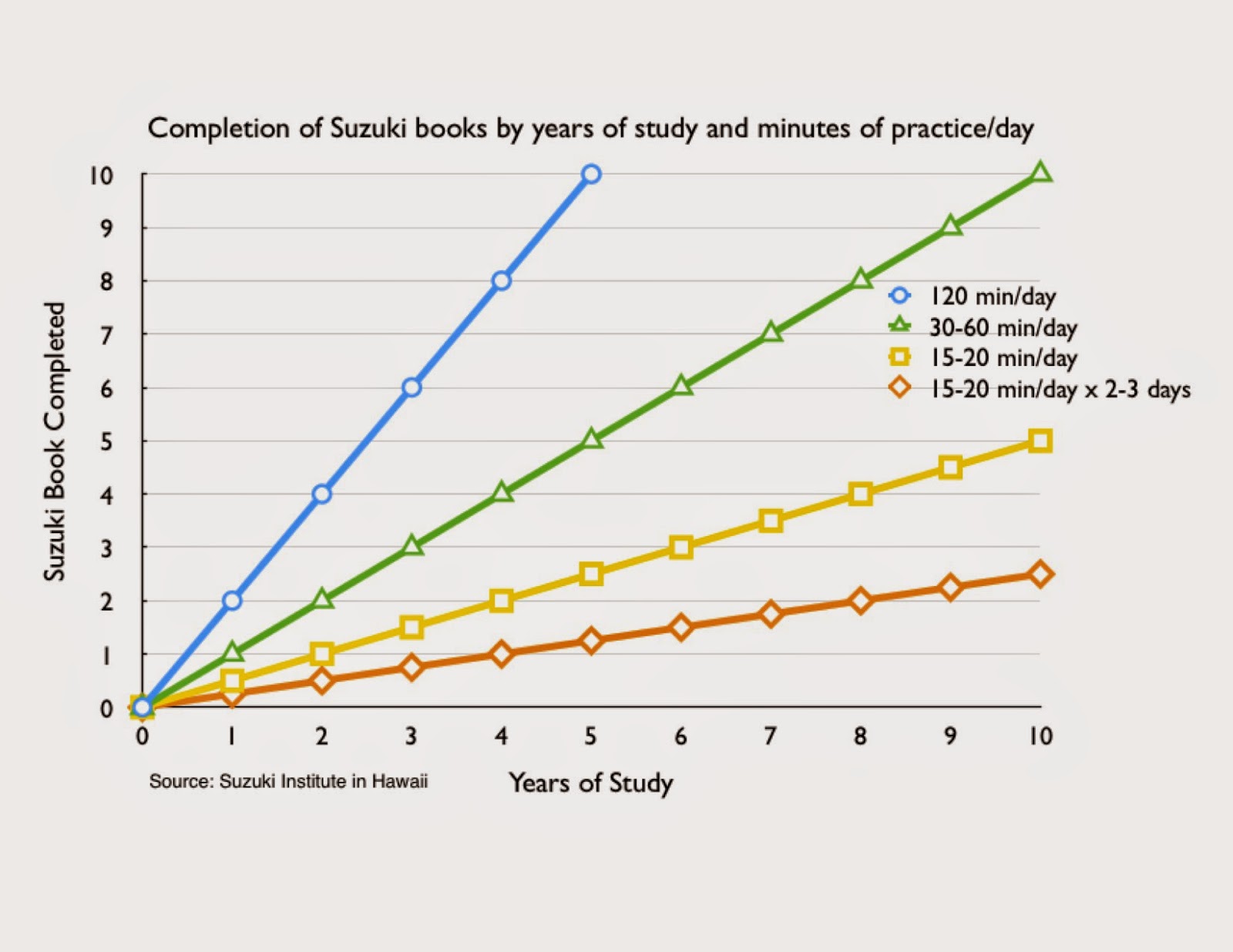

People who practice (and practice is a key word here) a growth mindset believe abilities can be cultivated and improved through effort, hard work and persistence. When presented with an obstacle, those practicing a growth mindset tend to rise to the challenge. Often, people of the growth mindset do not fear failure; instead, they view it as a chance to improve themselves. Growth mindset people have a love of learning as a result of the belief that abilities are developed, not inherent.

Ability vs. Accomplishment - Mindsets in Education

"Musical ability is not an inborn talent but an ability which can be developed. Any child who is properly trained can develop musical ability just as all children develop the ability to speak their mother tongue. The potential of every child is unlimited." —Shinichi Suzuki

In a school setting, a fixed mindset limits achievement and leads to inferior learning practices, such as cheating. However, achievements take clear focus, effort and many learning strategies.

PRAISE and the problem with it

Sometimes, by praising children, we diminish them. Praise should be given to effort and persistence rather than intelligence or talent. For example, if a child worked hard on learning a passage in a piece of music, then the hard work and effort must be recognized. However, if another child completed an assignment little effort and achieved the expected results, assign a more difficult task rather than praising him.

The growth mindset in education focuses on expanding the students' knowledge and ways of thinking and investigating the world as well as instilling a lifetime love of learning. Grades are not seen as an end in themselves, but as a means to grow. Grades don’t define the student but offer the opportunity to make an effort, learn and grow. The best thing we can do as teachers is teach children to love challenges, be intrigued by mistakes and enjoy effort and learning.

Every word or action sends a message of judgement and fixed traits or development. Dweck encourages giving praise from a growth mindset, praise that acknowledges hard work, achievements and effort, not intelligence or ability. In addition, when mistakes happen, feedback that helps fix the mistake is more constructive than judgements or excuses. Dweck's findings found that lowering standards for low-achieving students does not help. Rather, presenting tasks in with a growth mindset and offering feedback is more effective.

“Praise should deal, not with the child's personality attributes, but with his efforts and achievements.”—Haim Ginott

***

Though education is the most interesting facet of this research, I also found the research in sports and in the workplace very interesting. I've included a few tidbits from virg

Sports Findings

Finding #1: “Those with the growth mindset found success in doing their best, in learning and improving. And this is exactly what we find in champions” (98).

Finding #2: “Those with the growth mindset found setbacks motivating. They’re informative. They’re a wake-up call” (99).

Finding #3: “People with the growth mindset in sports took charge of the processes that brings success - and that maintain it” (101).

Business & Leadership and its Environment

A growth-mindset environment involves:

- Presenting skills as learnable

- Conveying that the organization values learning and perseverance, not ready-made talent and genius

- Giving feedback that promotes learning and future successes

- Presenting managers as resources for learning

- Fostering alternative ideas and constructive criticism - independent thinkers AND team players.

***

The implications of Dr. Dweck's work on music education and general education are profound! Even simply changing our language, we can help shape a child's mindset. This book report only covers a tiny bit of the intriguing information Dr. Dweck covers in her book. Her website offers a wealth of information beyond the book.

One of my goals as a teacher is to instill a love of learning as well as challenge students with opportunities to help them grow and develop their ability. Just as Dr. Suzuki repeated over and over again, the potential of every child is unlimited, we just have to help them and give them the tools to grow talent and ability.

One of my goals as a teacher is to instill a love of learning as well as challenge students with opportunities to help them grow and develop their ability. Just as Dr. Suzuki repeated over and over again, the potential of every child is unlimited, we just have to help them and give them the tools to grow talent and ability.